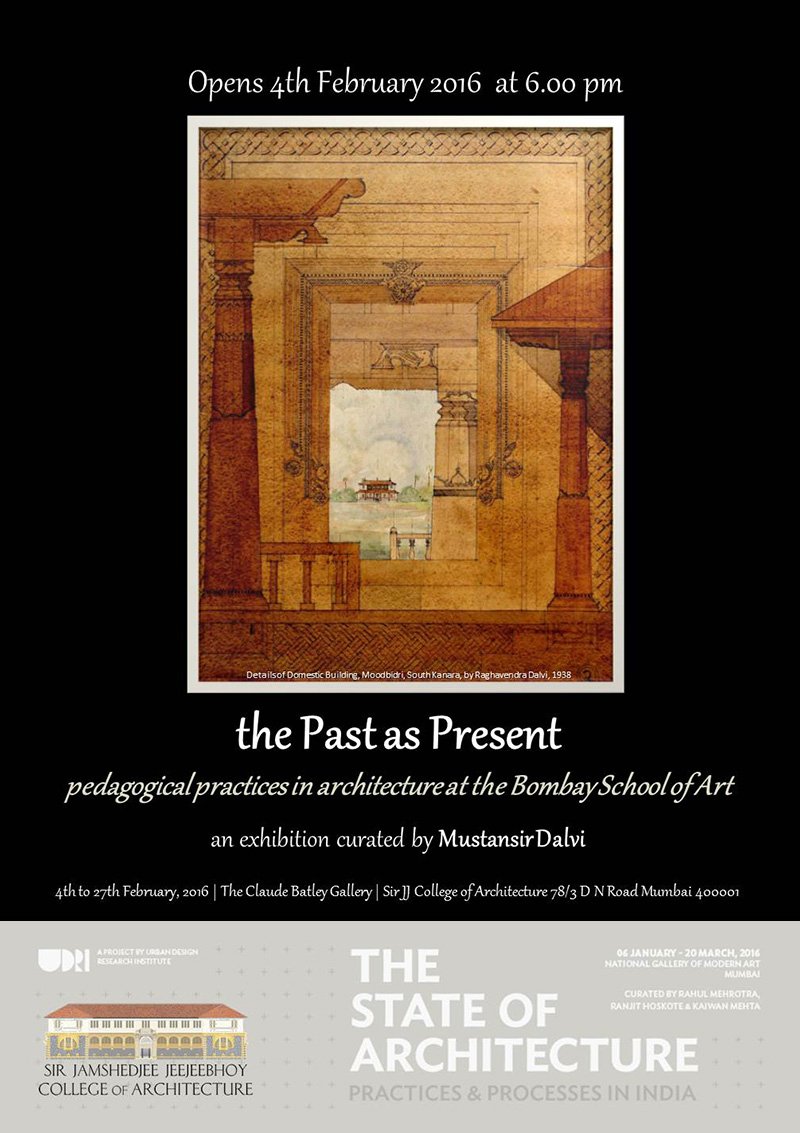

The drawings on display here are but a small sampling of a larger archive of measured drawings made by architecture students from the 20s, 30s and 40s and reflect both their creativity and the discipline of architectural drawing. These is a consistency to the craft and a clarity of rendering that allows one to appreciate the buildings themselves while taking delight in the drawings for their own sake. Interestingly, the one indicator that the drawings are of their own time can be seen in the choice of lettering, and the great variety of fonts chosen for the main titles of plates, all of which are contemporary to the 30s and 40s; some we can look back upon as classic Art-Deco lettering. This incongruence is unselfconscious, and telling for, outside the college, in practice these selfsame students would be designing architecture in the Style Moderne. Several of the students at the time would go on to become architects, artists and academics of note. Baburao Mhatre and Vasant Gore have medals endowed in their name, given out by the University of Mumbai even today. Solomon Reuben and Jai Ratan Bhalla would be noted academics, Reuben a longstanding head of Sir JJ College of Architecture. D. R. Chowdhari was, among others, a leading modernist architect of Bombay in the 1950s.

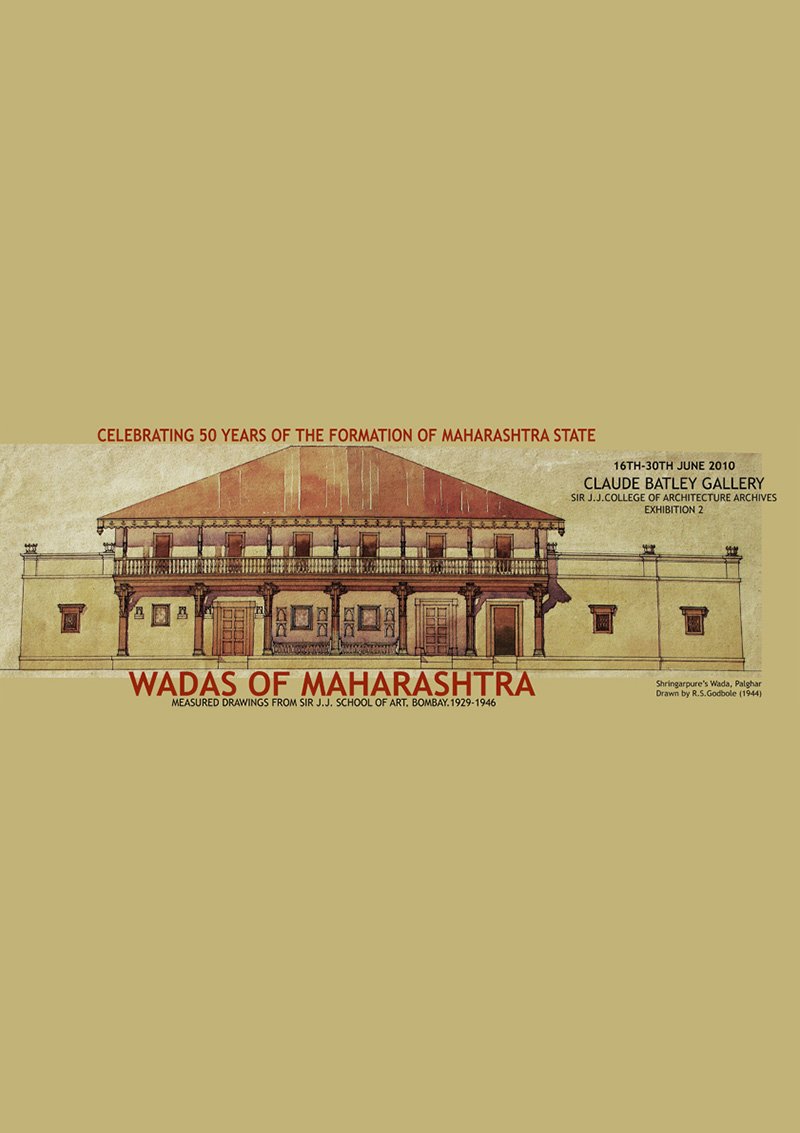

Maharashtra’s Wadas had their heyday in the Peshwahi and post-Peshwahi period of this state’s past. Many were built in the 18th and 19th century for politically or financially powerful families or officials of state- Nana Phadnavis, the Rastes, the Gaikwads, the Thakurs and others built homes for themselves in cities significant to Maratha history- Pune, Nasik, Satara, Ahmednagar.

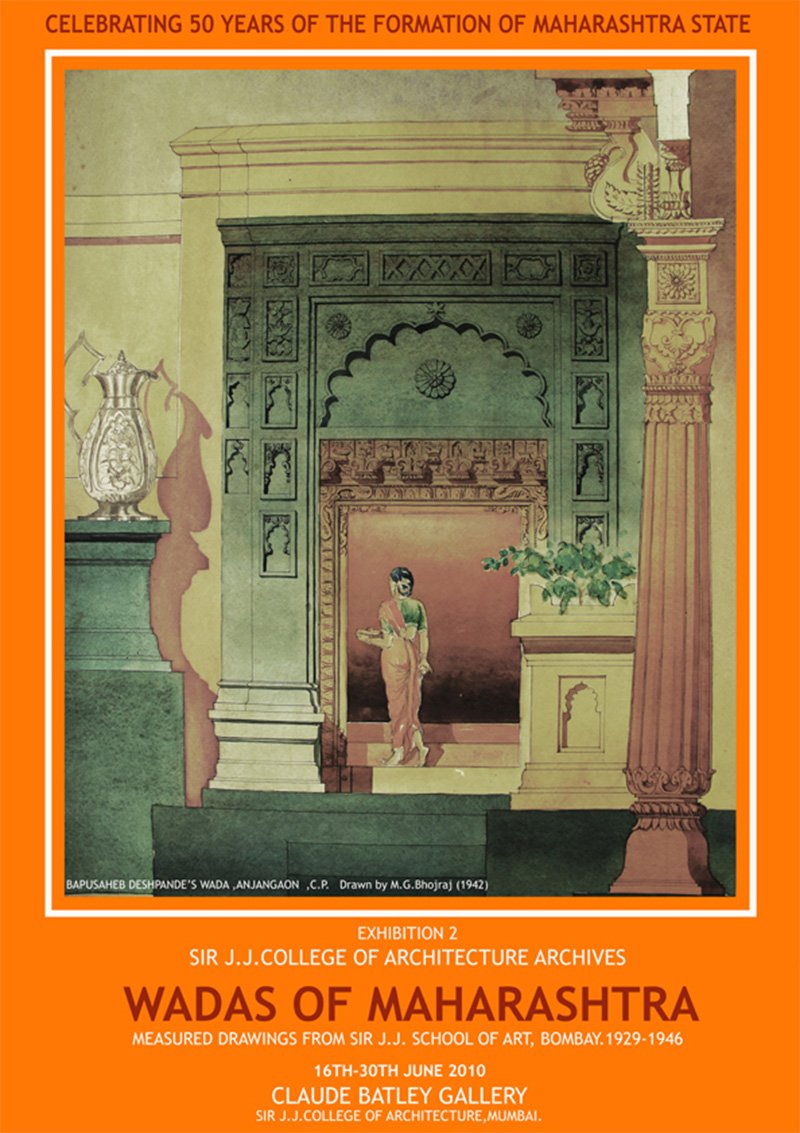

In this exhibition, two types of wadas are evident. One, built in the countryside, displaying donjon or fort-like characteristics, with bastions, high walls and the Buruj as a unifying element. The wada at Khed is a significant example. The other, town houses of the rich, displayed a more urban aspect, with woodcraft aesthetics on overt display on their facades, such as the wadas at Wai, Palghar and Poona. Both types had much in common; built around colonnaded courtyards, with outer walls largely unadorned, and with the Mazghar as the main room for reception and recreation. Also included in this exhibition are examples of Wadas from outside the state- from Baroda, Patan and Ujjain that reflect the influence of this typology beyond the confines of the Deccan. An interesting carry forward of this building form is seen in a town house from the 19th century in Phanaswadi , Bombay, where several of the ‘wada’ elements are compacted, yet visible, like the decorative frontage and the sloping roof (now modulated with dormer windows) .

These drawings are an important legacy. As is evident by photographs taken by the exhibition team in April 2010 to document the current state of some of these buildings, we are struck by the decrepitude of these structures today. Many of these Wadas have long vanished, the real estate on which they were situated having far greater value than their architectural heritage. Some Wadas, in the process of being brought down, have had their elemental parts dispersed and reinstalled in contemporary walls and ceilings, recycled, to mere showpieces, a hollow remnant of what once were consistent architectural schemes. A doorway here, a lintel there, a column or a bracket elsewhere are all that remain of these noble buildings. Their absence is telling of the way in which we have chosen to remember our built heritage.

One of the intentions of these documentation exercises was to ‘restore’ the Wadas, even if only on the drawing board, to the pristine state in which they were first built. Documentation and ‘Restoration’ went had in hand in the production of these plates. It is evident that three fourths of a century ago these (documented) Wadas were already facing the effects of time and change.

Several parts of these complexes were already in a state of ruin, with collapsed roofs and walls. Indicated by colours in the drawings- black for documented and red for ‘restored’, existing footprints of collapsed portions and architectural details extant elsewhere are sensitively adapted to ‘build-up’ complete edifices. Looking at the sparse remains of several of these Wadas today, these and other drawing present in the Sir JJ College of Architecture Archives may, in fact, be the only documents left that give us an authentic glimpse our state’s lost past. One should, therefore, celebrate the efforts and the foresight of these teams who documented the Wada heritage of Maharashtra, and who have left us with material that may actually aid any serious effort at conservation in the future.

Prof. Mustansir Dalvi

1st May 2010, Mumbai